Beethoven in 1823 |

Franz Liszt, 11, was presented to Beethoven. Thayer (846-847) goes as far as featuring the Hungarian composer's later (entirely correct?) recollection that Beethoven actually attended the concert and was supposed to have lifted the 11-year-old up and kissed him.

Schuppanzigh returned to Vienna after an absence of seven years. He gave a concert on May 4th. By June 14th, the quartet meetings were resumed with Holz, Weiss and Linke (Thayer: 853).

Beethoven spent the summer in Hetzendorf. During his stay there in the villa of Baron Müller-Pronay, while he worked on the completion of the Ninth Symphony, he also battled with ill health again, complaining of eye soreness.

Fidelio had been produced by Carl Maria von Weber in Dresden. Beethoven received a fee of 40 ducats from it. Weber also visited Beethoven in Baden in September and was, perhaps surprisingly, in light of the usual animosity between the two composers, received very cordially.

By this time, the management of Beethoven's financial affairs was in the hands of Anton Schindler and Johann van Beethoven, with Count Moritz Lichnowsky also giving advice here and there. In order to overcome financial difficulties in paying monies Beethoven still owed the Vienna music publisher Steiner & Co., he sold off one of his bank shares. These difficulties are mentioned in Thayer as an impetus for the Missa Solemnis subscription plan.

This year ended with Beethoven working on the completion of the Ninth Symphony, while his eyes continued to bother him (which would last until late March 1824). The completion date of the Ninth Symphony that was given by Schindler is February 1824 (Thayer: 886).

To complete the recordings for the year 1823, we should first return to Beethoven's creative plans and activities besides the completion of the Ninth Symphony:

-- He spoke again of a "second mass";

-- He also had plans for a new opera and wanted a subject from the antique world. The most likely co-operation on this project emerged with the Viennese playwright, Franz Grillparzer. Subjects discussed were the Bohemian legend of Drahomira and Melusine. Grillparzer and Beethoven held several conferences, also in Hetzendorf. Beethoven would ultimately not pick up on this idea, while Grillparzer later had the honor of writing the famous and insightful oration for Beethoven's 1827 funeral;

-- Another "creative idea" that was realized in 1823 were the 33 variations to a waltz by Anton Diabelli. They were completed by March or April, 1823, and dedicated to Antonie Brentano.

In completing this section of Beethoven's life, we will only trace the events of 1824 up to and including the premiere of the Ninth Symphony and parts of the Missa Solemnis as well as the after-effect of that premiere on the composer and his "associates" in this project. Anton Schindler, who was not only a witness but an active agent in the first performance of the Ninth Symphony, is the main narrator of its history.

Beethoven is reported as having had little confidence in the Viennese audience who at that time adored Rossini's operas. The following conversation between him and the ultimate two female lead singers, Karoline Unger and Henriette Sontag, on January 25th, was noted down in one of the conversation books, in which Beethoven's answers were verbal and not recorded:

Karoline Unger: "When are you going to give your concert? When one is once possessed by the devil, one can be content.

--------"On a regular day in lent, when 3 or 4 take place, would be best."

--------"If you give the concert, I will guarantee that the house will be full."

--------"You have too little confidence in yourself. Has not the homage of the whole world given you a little more pride? Who speaks of opposition? Will you not learn to believe that everybody is longing to worship you again in new works? O obstinacy!"

At his lowest point, Beethoven even sought to have the two works performed in Berlin. On hearing of this, his Viennese friends and admirers addressed a lengthy memorandum to him, urging him to perform his works in Vienna, soon. The declaration was signed by many Viennese dignitaries. However, rumors were spread that Beethoven himself had instigated this appeal. Beethoven was, of course, disgusted and dismayed. When the appeal was presented to him in person, however, it did sway him to allow the works being premiered in Vienna.

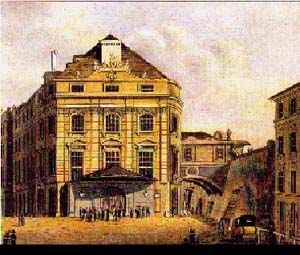

During the decision-making process as to which theater should be chosen, Beethoven was at first hesitant and, when urged on to decide, became obstinate again and saw a plot against him developing behind his back. By April, the Kaertnerthor-Theater was finally decided on with Umlauf and Schuppanzigh directing. May 7th was then formally confirmed as the date for the premiere. To be played were the new Overture, Op. 124, the Mass in D and the new Symphony. Realizing that this was too long, the Gloria and Sanctus were omitted from the Mass. One more obstacle was the church authorities' opposition to a Mass being performed in a theater. Beethoven wrote to the censor, Sartorius, that the three pieces from the Mass were to be listed as Hymns (Thayer: 906). Although this failed, by appealing to the Police President (with the help of Count Lichnowsky), the performance was finally approved.

Kärtnertor-Theater |

During the rehearsals in Beethoven's apartment, Unger pleaded with him to ease the strain on the high female voices, but to no avail. Her laconic reply to Henriette Sontag: "Well, then we must go on torturing ourselves in the name of God!" (Thayer: 907).

At the final rehearsal on May 6th, Beethoven was "dissolved in devotion and emotion" at the performance of the Kyrie, and after the Symphony " . . . Embraced all the amateurs who had taken part" (Thayer: 907).

While the theater was crowded on May 7th, the Imperial Box was empty. The Emperor's family was not in Vienna, and Archduke Rudolph was in Olmütz. Thayer reports that:

"The performance was far from perfect. There was a lack of homogenous power, a paucity of nuance, a poor distribution of lights and shades. Nevertheless, as strange as the music must have sounded to the audience, the impression which it made was profound, and the applause which it elicited enthusiastic to a degree. . . . At one point in the Scherzo, the Ritmo di battate, the listeners could scarcely restrain themselves, and it seemed as if a repetition then and there would be insisted upon. To this Beethoven, no doubt engrossed by the music which we was following in his mind, was oblivious. Either after the Scherzo or at the end of the Symphony, while Beethoven was still gazing at his score, Fräulein Unger, whose happiness can be imagined, plucked him by the sleeve and directed his attention to the clapping hands and waving hats and handkerchiefs. Then he turned to the audience and bowed" (Thayer: 909).

Subsequent conversation book entries of those who attended the concert confirm the tenor of the above:

"Never in my life did I hear such frenetic and yet cordial applause."

--------"Once the second movement of the Symphony was completely interrupted by applause . . . And there was a demand for repetition."

-------"The reception was more than imperial."

--------" . . . For the applause burst out in a storm four times. At the last there were cries of Vivat!"

--------"When the parterre broke out in applauding cries the fifth time, the Police Commissioner yelled 'Silence!'"

"Court only 3 successive times but Beethoven 5 times."

--------(Beethoven): "My triumph is now attained. For now I can speak from my heart. Yesterday I still feared secretly that the Mass would be prohibited because I heard that the Archbishop had protested against it. After all, I was right in at first not saying anything to the Police Commissioner, by God, it would have happened!"

Beethoven's nephew Carl was to go to the box office to receive the money in the presence of his uncle, as Beethoven wanted him as a witness to the transaction. The profit for Beethoven was meager: only 420 florins remained of the receipts after all costs, from which some petty expenses were yet to be paid. Beethoven vented his anger at all those who had helped in staging the event at the dinner he had invited them to. Umlauf, Schuppanzigh and Schindler walked out of it.

A second concert was held on Sunday, May 23rd. As the weather was very warm and nice, the theater was only half full. Duport, the organizer, had to suffer a deficit of 800 florins, while Beethoven had been guaranteed 500 florins.

In the meantime, Beethoven had sent a copy of his Symphony to the Philharmonic Society in London and had, on April 24th, 1824, receipted the sum of fifty British Pounds.

Financial gain and re-affirmation of old friendship ties not having been the ultimate outcome of Beethoven's efforts of composing and staging his two latest public masterpieces, we may wish to return in our minds to the composer's own notions on the presence or absence of joy in his life. It appears, then, that Beethoven had appeased his outcry in the Heiligenstadt Will,

"When, O Godhead, will I be able to feel it again in the temple of nature and men--never--no--that would be too cruel",

himself by the only means available to him, as he already hinted at his capacity to bring joy to himself and to others:

"O blissful moment, how fortunate I consider myself that I can summon you, create you myself",

in his 1801 letter to Wegeler, thereby creating his very own day of joy at the May 7th, 1824, premiere of his works.

In this context, the words Friedrich Schiller, the writer of the Ode to Joy, had put into the mouth of Marquis Posa in his play Don Carlos, which he wrote at the same time as the Ode, come to mind:

"To me, however, virtue has a value of its own. This happiness . . . I would create it myself, and joy would be to me and my own choice, what should only be my duty."