Depiction of Beethoven's Study at the Schwarzspanierhaus |

The Quartet in a minor was first performed publicly on November 6th in the Music Society's room at the Roter Igel in a benefit concert for Josef Linke. This concert, which also featured a Carl Maria von Bocklet as pianist, playing the Trio in B-flat major, was a great success. Schuppanzigh received permission to perform the Quartet again on November 20th.

During late summer and fall of 1825, Beethoven also wrote the next Quartet in B-flat, Op. 130, which was completed in November. This work was sold to Artaria and did not appear until May, 1827. It was first performed publicly in March, 1826, with the Great Fugue as its original finale.

The year 1826 would see the creation of Beethoven's greatest String Quartet, the Quartet in c-sharp minor, Op. 131, that of his last String Quartet, Op. 135, as well as a new last movement to Op. 130, all of which took place in the midst of Beethoven's constant worries over and arguments with Carl about his conduct. To this, Thayer has to say: "That he could continue to write amidst all the disturbing circumstances of this year in the higher and purer regions of chamber music was a source of admiration and wonder to his friends." (Thayer: 973).

Those who were in closest contact with Beethoven during this time were, of course, Holz as his private secretary, Stephan von Breuning and his family, Schindler here and there as a partly jealous observer (of Holz) and advisor, and last, and maybe least, his brother Johann. There were also conversation book entries to be found of Schuppanzigh, Kuffner, Grillparzer, Abbé Stadler and Matthias Artaria.

Near the end of January, Beethoven's old abdominal complaints returned. He also complained about his eyes. He was told to refrain from alcohol and coffee. He appeared to have improved during March.

At this time, Beethoven also became interested in the first performance of his Leibquartett,Op. 130. It was performed on March 21st. Most of the movements, particularly the moving Cavatina and the Danza alla Tedesca, were immediately liked by the audience. The second and fourth movements had to be repeated. The Great Fugue, its finale, however, was not understood. Of the Cavatina, Holz reported that "it cost the composer tears in the writing and brought out the confession that nothing he had written had so moved him; in fact merely to revive it afterwards in his thoughts and feelings brought forth renewed tributes of tears." With respect to the Great Fugue, Beethoven agreed to write a new ending for the quartet and to let the Fugue stand as a separate work, Op. 133.

With respect to Dembscher's desire to have this Quartet performed at his house, Beethoven refused to give him the score as the former had not attended Schuppanzigh's premiere. A "compensation" of 50 florins was arrived at with Dembscher asking, "Must it be?", and Beethoven humorously supplying the canon, "Es muss sein!" (It must be). Out of this joke arose the finale of his last quartet, Op. 135.

In May, Beethoven suffered from anxiety in not receiving from Prince Gallitzin payment for his second and third quartets of the series that he had already sent to Russia. It took until November to receive an informative reply from Russia in which Gallitzin explained that he had suffered great losses from several bankruptcies but that he would send the payment, soon. Beethoven was made to sign one last letter of appeal for his money on his deathbed and did not see it arriving during his life.

In his ongoing negotiations with respect to Op. 131 with Artaria, Beethoven finally turned about and gave it to Schott & Sons in Mainz.

With respect to the history of the creation of Op. 131, Thayer mentions first notes of it appearing in a December 1825 conversation book, while Beethoven was busy writing the work during the first part of 1826. It is not known for certain if the work was ever publicly performed during Beethoven's lifetime. On March 28th, the composer asked of Schott 60 Gold Ducats for it. The score was finally given to Schott's agents in Vienna on August 12th, and published in June, 1827. In a letter of Beethoven to Schott of February 22nd, 1827, mention was made that the work was originally to be dedicated to Beethoven's friend and admirer, Johann Wolfmayer, but in his March 10th , 1827, letter to Schott, Beethoven asked them to change the dedication to Baron Joseph von Stutterheim, Lieutenant Field-Marshal, whose significance in Beethoven's and his nephew Carl's lives would become apparent in late 1826.

In the midst of Beethoven's plans to finally spend the rest of the warm season either in Ischl or in Baden, an event took place which turned his life upside down: his nephew Carl's failed suicide attempt. In order to trace the development leading up to this event, we have to "track back" to a certain extent.

While Carl's spring 1825 beginnings at the Polytechnicum showed some promise, he also needed a tutor to catch up for having entered the term late. It appears that he may never have been able to entirely achieve that. Beethoven estimated that he would spend 2,000 florins a year for Carl's schooling, lodging and tuition, and wanted to see some positive results for it, while Carl's real occupational aim was that of becoming a soldier. His change from classical language studies to business studies was a compromise that did not work to either his or Beethoven's advantage.

Beethoven had Schlemmer, at whose house Carl lodged, confirm to him as to whether Carl spent his evenings there, studying, or if he went out. Schlemmer confirmed that Carl was always at his lodgings after classes and at night and that any of his amusements, such as playing billiards, must have taken place in lieu of his going to classes. During the carnival season of 1826, Beethoven was almost anxious enough to personally supervise Carl's attendance of a ball, should he decide to go to one. Holz agreed to observe Carl in Beethoven's stead. Beethoven also wanted Carl to move back in with him and only reluctantly agreed to his staying at Schlemmer's house. Their conversations now seemed to mainly consist of Beethoven's sermons and reproaches and Carl's self-defenses. Johann van Beethoven also tried to intervene, on the one hand speaking for the boy, on the other strongly advising Beethoven to see to Carl's immediate employment on completion of his course in summer. Beethoven also mistrusted Carl in money matters and wanted to see receipts for his expenses. Beethoven visited and reproached Carl at Schlemmer's several times, on which occasion, at least once, Carl appears to have grabbed his uncle in a violent reaction which Holz' entering interrupted. As if Beethoven could foresee the outcome of this development, he urged Carl on thus in a letter to him:

"If for no other reason than that you obeyed me, at least, all is forgiven and forgotten; more today by word of mouth. Very quietly--do not think, that I am governed by anything but thoughts of your well-being, and from this point of view judge my acts--do not take a step which might make you unhappy and shorten my life--I did not get to sleep until 3 o'clock, for I coughed all night long--I embrace you cordially and am convinced that soon you will no longer misjudge me; I thus judge your conduct yesterday--I expect you without fail today at one o'clock--Do not give me cause for further worry and apprehension--meanwhile farewell!

Your real and true father."

"We shall be alone for I shall not permit Holz to come--the more so since I do not wish anything about yesterday to be known--do come--do not permit my poor heart to bleed any longer" (Thayer: 994).

Beethoven's monitoring of Carl went as far as coming to pick him up from school. Schindler reports of Carl's reply to the rebuke by his teachers: "My uncle! I can do with him what I want, some flattery and friendly gestures make things all right, again, right away." Alas, during the last days of July, Beethoven received news that Carl had vanished and intended to take his life. The reasons Carl gave for this step were his debts. Beethoven had Holz go after Carl to detain him, but Carl gave him the slip. Carl pawned his watch on Saturday, July 29th. He bought two pistols, powder and balls. He drove to Baden, spending the night with writing letters to his uncle and to his friend Niemetz. On Sunday he climbed up the ruins of Rauhenstein in the Helenenthal and fired both pistols at his left temple. The first bullet missed, and the second only ripped his flesh and grazed the bone, but did not go into his skull. A coach rider found Carl and brought him to his mother's house in Vienna, where Beethoven found him. Holz, who went with Beethoven, reported the matter to the police and Beethoven went home, while a doctor already looked after Carl. Police transported Carl from his mother's house to the general hospital on August 7th. As was usual in such cases, a priest was ordered to provide religious instruction to the suicide candidate and to extract a conversion. Holz reported to Beethoven that Carl had grown tired of life which he perceived differently from his uncle, and to the Police Magistrate Carl said that Beethoven "tormented him too much" and that "I got worse, because my uncle wanted me to be better."

While the event began to pave the way for Carl's personal career choice, it had a devastating effect on Beethoven which soon had him, aged fifty-five, according to Schindler, look like a man of seventy. A decision had to be reached as to Carl's future. Stephan von Breuning, a court councillor in the war department, advised on a military career and also suggested that Beethoven relinquish his guardianship. In the meantime, Beethoven had already begun to work on the last String Quartet, Op. 135. The question arose as to where Carl should recuperate after his dismissal from the hospital, while Stephan von Breuning arranged for Carl to enter the regiment of Baron von Stutterheim as a cadet on his full recovery, and he also agreed to act as co-guardian of Carl in lieu of Professor Reisser of the Polytechnicum who had laid it down.

Finally it was decided that Beethoven and Carl should spend the time Carl needed to recuperate at Johann van Beethoven's estate in Gneixendorf. Johann was in Vienna at that time and offered them that choice. On September 28th, they set out for there. It was only to be a short visit, but turned into a two-month-stay.

Beethoven's Room at Gneixendorf |

Beethoven arrived in Gneixendorf already in a serious state of health. He did also not enjoy the company of his brother and sister-in-law. A servant named Michael was assigned to him whom he grew to trust. On the occasion of Michael's falling out of graces with Therese van Beethoven, the composer urged her to re-hire the just fired Michael. From then on, Beethoven stayed in his room for his meals. He also walked through the fields around Gneixendorf, gesticulating, humming, beating tact to the music in his "inner ear". Thus Op. 135 was completed in Gneixendorf as well as the new last movement of Op. 130. The date on the autograph of Op. 135 is October 30th, on which Johann took it to Vienna. The new finale for Op. 130 was delivered by Haslinger to Artaria on November 25th. Beethoven's relationship with Carl was still as touchy as could be expected, with both acting "in character", as usual.

Beethoven's health worsened in Gneixendorf. Soon, he could only eat soup and soft-boiled eggs, but still drank wine and contracted diarrhea. Towards the end of November, he had lost his appetite, altogether, complaining of thirst. He also developed edemous feet. All of this pointed to a serious liver disease. Johann now also became concerned with Carl's future and urged Beethoven to take him back to Vienna so that he could join his regiment soon, but did so in a letter and not in a personal argument. Beethoven's state of mind was in such a disarray at that time that he even asked his brother to leave his entire estate to their nephew Carl, thereby cutting out Therese. As for the vehicle in which they returned to Vienna, one should not rely on Schindler's biased interpretation that Johann had denied Beethoven the use of his carriage. Nevertheless, it can be assumed that they traveled in an open wagon, as Beethoven later stated to his physician, Professor Wawruch.

They arrived back in Vienna on Saturday, December 2nd, with Beethoven in a fever from a chill he had caught in their overnight stay in an unheated room. The circumstances of Carl's delayed summoning of a doctor for his uncle are anything but clear so that we have to refrain from laying the blame on Carl. Dr. Braunhofer and Dr. Staudenheim apologized for not being able to attend on Beethoven. On the third day of his fever, Professor Wawruch of the General Hospital took Beethoven on as a patient. He treated the inflammation and lowered his fever. On the seventh day, Beethoven could get up and read and write. Now he found time to answer Wegeler's letter of a year ago. On the eight day, however, Wawruch found his patient worse after a severe colic attack. Dropsy developed from then on. The illness progressed to nightly suffocation attacks in the third week. Johann, who had come to Vienna on December 10th, attended to his brother as did Carl as long as he was still in Vienna. Stephan von Breuning also attended, as did Holz and Schindler. On December 20th, Beethoven's abdomen had to be tapped to release the water. This was performed by Dr. Seibert, chief surgeon at the General Hospital. Present were also Johann and Carl, as well as Schindler. Dr. Seibert's comment on Beethoven's endurance was, "You bore yourself like a knight." One joyful occasion in this gloom was the arrival of the collected works of Handel Stumpff had now sent Beethoven. Gerhard von Breuning vividly recalls this event in his book. The boy was now a daily visitor who cheered Beethoven up.

Stephan von Breuning had finalized the arrangement for Carl to enter von Stutterheim's regiment. Carl left Vienna on January 2nd, 1827, and would never see his uncle again. On January 3rd, Beethoven wrote yet another letter to his lawyer, Dr. Bach, in which he reiterated his declaring Carl as his sole heir. On January 8th, Beethoven was tapped a second time. The patient had by now grown impatient with Wawruch. When he entered the room, Beethoven would turn around in his bed towards the wall, commenting, "Oh, the ass!" He requested that Dr. Malfatti, his former physician, be called in. The composer had had a falling-out with Malfatti ten years prior to that. They were finally reconciled after initial hesitation by Malfatti. The latter prescribed ice punch and the rubbing of Beethoven's abdomen with ice. While this treatment brought some relief at first, its abuse by Beethoven led to a "violent pressure of the blood on the brain . . . Began to wander in his speech . . . And when . . . Colic and diarrhea resulted, it was high time to deprive him of this precious refreshment" (Thayer: 1031). Malfatti did not take over from Wawruch as Beethoven's main physician, however. Beethoven had to be tapped a third time on February 2nd.

The conversation book entries of February show the names of Haslinger, Streicher, the writer Bernard and the singer Nanette Schechner. A letter from Wegeler arrived on February 1st. Beethoven replied on February 17th. On February 18th, he also replied to his old bed-ridden friend, Baron Zmeskall's inquiry. In his letter of Feburary 8th, Beethoven thanked Stumpff of London for the gift of the Handel edition. He also mentioned his writing to Charles Smart and Ignaz Moscheles for financial aid from London. On Stumpff's initiative, the Philharmonic Society sent Beethoven the sum of 100 pounds in financial support during his illness.

During February, Beethoven became very melancholic over the outcome of his illness, over financial worries, and over the neglect of Carl's writing to him. Friends visited to take his attention away from his melancholy.

The fourth tapping took place on February 27th. To Wawruch's attempt at cheering him up, Beethoven replied, "My day's work is finished. If there were a physician who could help me 'his name shall be called wonderful'" (Thayer: 1038). On March 1st, Beethoven wrote to Schott in Mainz and also asked for a delivery of Moselle wine. On March 18th, he gratefully acknowledged the receipt of the 100 lb. From London.

In March, no-one denied Beethoven the simple pleasures of wine and good food, anymore, as the outcome of his illness was clear by now. Baron Pasqualati, von Breuning and Streicher sent their gifts of that kind. During those days, in addition to Handel's works, Beethoven also studied those of his young Viennese colleague, Franz Schubert, crying out, "truly a divine spark dwells in Schubert" (Thayer: 1043). With his friend, Anselm Hüttenbrenner, as Thayer reports, Schubert allegedly visited Beethoven eight days before his death. Johann Nepomuk Hummel also visited on March 8th.

It was now time to bring his affairs into order. His last written statement with respect to his Will reads as follows:

"My nephew Carl shall be sole heir, but the capital of the estate shall fall to his natural or testamentary heirs.--

Vienna on March 1827

Ludwig van Beethoven" (Thayer: 1048).

All other signatures for more particular documents with respect to his estate that had been drawn up before had to be obtained with great difficulty, as from about March 20th on, Beethoven was already very weak. Schindler reports that on March 23rd, after the signing of his Will, Beethoven is to have said, "plaudite, amici, comoedia finita est", implying that nothing could be done for him, anymore.

As to Beethoven's submitting to and receiving the last rites, Anselm Hüttenbrenner recalled that "Beethoven was asked in the gentlest manner by Herr Johann Baptist Jenger and Frau van Beethoven, wife of the landowner, to strengthen himself by receiving Holy Communion . . . On the day of her brother-in-law's death, Frau van Beethoven told me that after receiving the viaticum he said to the priest, 'I thank you, ghostly sir! You have brought me comfort!" (Thayer: 1049).

Around one o'clock on March 24th, the shipment of Moselle wine had arrived. Beethoven, looking at the bottles, mumbled, "pity, pity, too late!" These were his last reported words. He was given spoonfuls of the wine. Later that day, he fell into a coma which would last for two days. Anselm Hüttenbrenner, who was present when Beethoven died on March 26tharound five-thirty in the evening, recalls:

"There came a flash of lightning accompanied by a violent clap of thunder, which garishly illuminated the death-chamber . . . Beethoven opened his eyes, lifted his right hand and looked up for seconds with his fist clenched and a very serious, threatening expression . . . When he let the raised hand sink to the bed, his eyes closed half-way. My right hand was under his head, my left rested on his breast. Not another breath, not a heartbeat more!" (Thayer: 1051).

While Hüttenbrenner was present during Beethoven's last moments, Schindler and von Breuning had gone to make arrangements for his burial in the nearby Währing cemetery. The day after, von Breuning, Schindler, Johann van Beethoven and Holz gathered in the apartment to look for Beethoven's papers and for the seven bank shares. Johann van Beethoven insinuated that the search was a sham. In a rage, von Breuning left the house and returned later. The shares were then found in a secret drawer of Beethoven's cabinet, along with his letter to the Immortal Beloved.

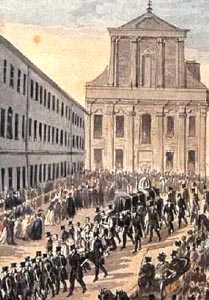

Beethoven's funeral took place at three o'clock in the afternoon, on March 29th. A crowd of possibly over 10,000 (and maybe not quite 20,000, as Gerhard von Breuning reports) had gathered in front of the Schwarzspanierhaus to bid farewell to him.

Funeral Procession |

Eight Kapellmeisterwere the pallbearers, among which were Hummel and Seyfried. Among the torchbearers were the actor Anschütz, the journalist and Beethoven friend Bernard, his former pupil Carl Czerny, Grillparzer, Haslinger, Franz Schubert, Andreas Streicher, Schuppanzigh, Wolfmayer and others.

Anschütz read Grillparzer's funeral oration in front of the gate to the Währing Cemetery. Part of it reads as follows:

"He was an artist, but a man as well. A man in every sense--in the highest. Because he withdrew from the world, they called him a man-hater, and because he held aloof from sentimentality, unfeeling. Ah, one who knows himself to be hard of heart, does not shrink! The finest points are those most easily blunted and bent or broken. An excess of sensitiveness avoids a show of feeling! He fled the world because, in the whole range of his loving nature, he found no weapon to oppose it. He withdrew from mankind after he had given them his all and received nothing in return. . . . Thus he was, thus he died, thus he will live to the end of time."